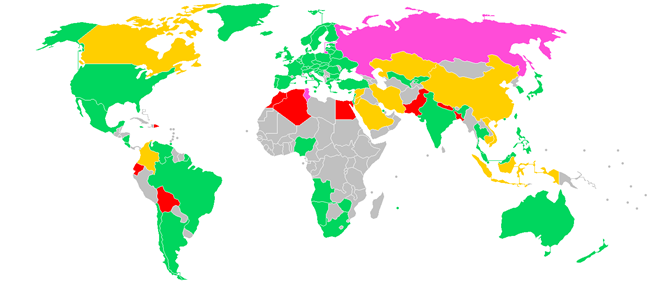

Figure 1: Legal status of bitcoin

The scope, reach and diversification of cryptoassets has immensely expanded since the introduction of Bitcoin in 2008. This expansion has happened well beyond the scope of the regulatory and legal frameworks in place, including the regulatory sticking plasters introduced as a response.

Four trends are currently shaping the crypto-space: (i) increasing sophistication and diversification of products available to investors, and their introduction in both retail and institutional portfolios; (ii) the progressive expansion of payment systems using the technology of cryptoassets; (iii) the planned introduction of global stablecoins in international multipurpose platforms, as is the case of Facebook’s Libra; and (iv) Central Bank Digital Currency projects gaining traction under the technological change brought by cryptoassets, as a reaction to global stablecoins, and in response to the policy challenges posed by the most recent economic crisis.

These four trends have raised questions about the appropriate regulatory perimeter and the ability of the existing regulatory architecture to adapt to the fast-changing conditions, while shaping the market and providing protection to consumers and investors.

Regulatory responses have been largely heterogenous across jurisdictions and have seen the interventions of several types of authorities from supranational to domestic and judiciary. Only a small number of countries – mainly emerging or frontier economies – have applied implicit or explicit bans on cryptoassets, whose enforcement is often questionable (see Figure 1 above). Most regulators have acknowledged that cryptoassets are at the core of the fintech revolution, and have high potential to reshape financial and payment services providing values to consumers and investors.

Capturing this positive attitude, a 2019 IMF policy note on the regulation of cryptoassets (Cuervo et al 2019) observed that:

"Regulation should not be seen as stifling innovation, but rather as building trust. As for the more traditional financial sector, regulation can instil trust in the business and foster a safer development of the sector by providing clear guidelines that remove uncertainty and thus foster confidence."

In this note, we provide a bird’s-eye view on the emerging regulatory landscape. We discuss why there is a need for regulation, what has to be regulated, who is in charge, and how regulation is emerging. A follow-up article will explore which norms have been implemented and their enforcement.

Why is there a need for regulation?

At the start of 2020, a report to the European Parliament estimated that “over 5,100 cryptoassets exist with a total market capitalisation exceeding $250 billion”, and remarked that the crypto space comprised of both lawful and unlawful markets (Houben and Snyers, 2020). It noted that, at the present, most of the legal use of cryptoassets takes place on exchanges for investment purposes. The illegal activities concern mainly but not exclusively the use of cryptoassets as payment instruments.

The same report pointed to five (plus one) main areas of regulatory concern that have emerged over time in relationship to the introduction and use of cryptoassets (see The Risk Landscape of Cryptoassets). We list these concerns as follows, from a micro to a macro level, but also in the timeline of them being discussed by regulators:

- A regulatory concern is the use of cryptoassets for financial crime, money laundering and terrorist financing risks (ML/TF risks). The fully digital, decentralised, easily transferable, and pseudonymous nature of cryptoassets makes them potentially suitable for financial criminal activities.

- A second concern relates to investor and consumer protection. Regulators consider cryptoassets to be potentially a risky investment and partially outside the scope of most financial services regulation in place. Hence consumers and investors may be unprotected if something goes wrong, and lack of any legal certainty.

- Third, cybersecurity risks are considered a major issue. Stolen cryptoassets, ransomware attacks, and the hacking of cryptoasset systems have shown the lack of robust security infrastructure in the market. In most jurisdictions, there are no specific laws that set out minimum standards for cybersecurity to be complied with by market operators in the crypto space.

- Fourth, several financial institutions are gaining exposure to cryptoassets or have started providing services relating to cryptoassets. Given the high volatility, such exposure can potentially pose macroprudential risks (see When Global Stablecoins Fail).

- The fifth area is related to the potential introduction of Central Bank Digital Currencies and their regulation (see A Primer on Central Bank Digital Currencies).

- The introduction of global stablecoins is an additional area and poses systemic challenges and risks to financial stability and monetary policy (see Stablecoins in the Financial Network).

What has to be regulated?

The first important step to understand regulation in the crypto market is to draw a taxonomy of assets, and define norms and policymakers’ competences. The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (2020) find that more than the 80% of surveyed jurisdictions have tried to draw a clear distinction between cryptoassets that qualify as securities and those that do not.2

A smaller set of jurisdictions use a finer classification, notably three main categories:

- payment assets / tokens that are primarily used as a means of payment;

- utility assets / tokens that grant holders access to a digital resource or service;

- securities assets / tokens that need to be considered as investment assets, similar in nature to traditional securities.

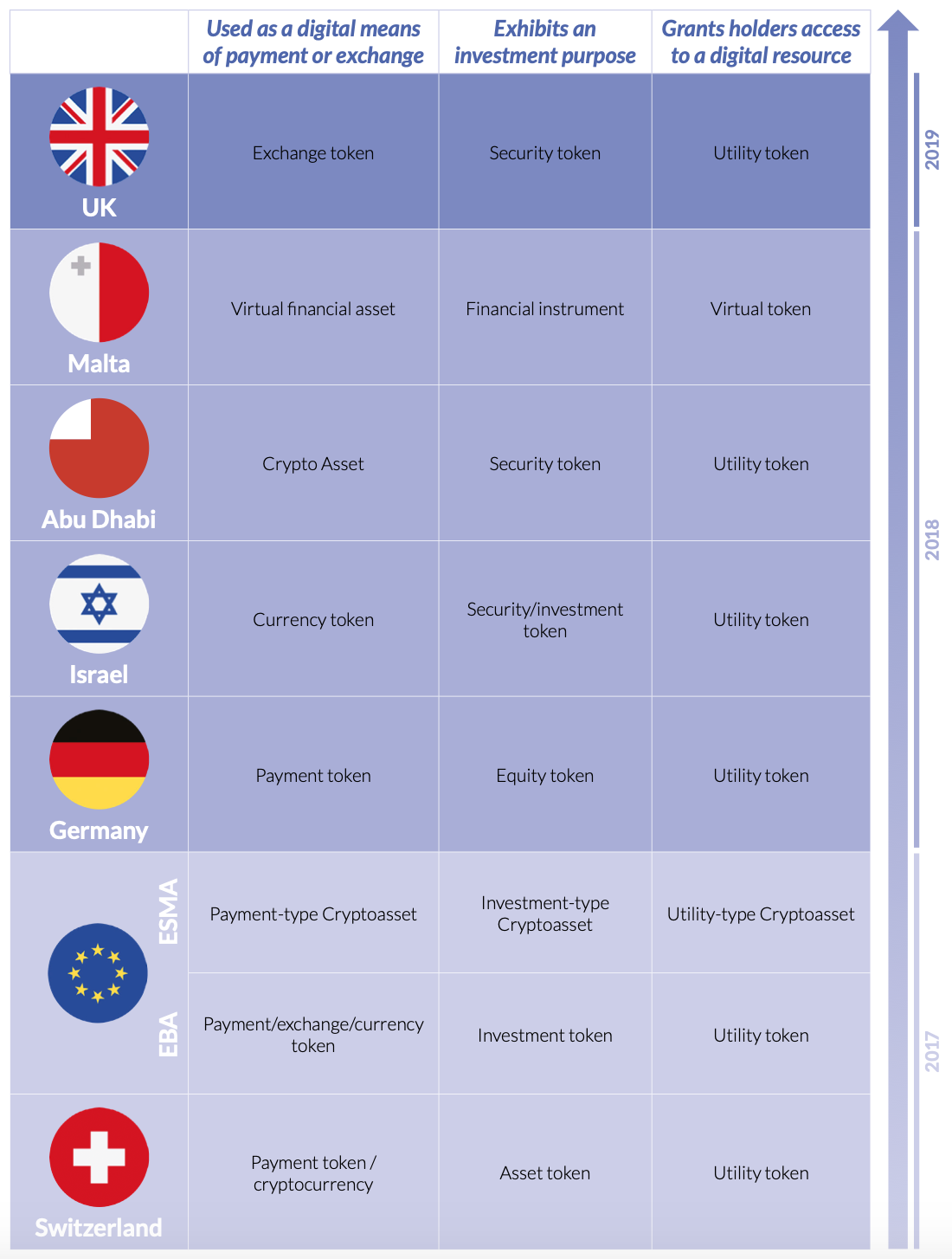

Table 1 below provides a few examples of these finer classifications and the jurisdiction-specific taxonomy adopted.

How is the security of a cryptoasset assessed? The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance highlight two possible approaches. The first is what is defined as a case-by-case examination approach, i.e. assessing the characteristic of each asset individually. This is by far the mostly adopted method around the world. The alternative is by employing a standard financial instrument test – as for example the “Howey Test” in the USA.3

These taxonomic distinctions are key to providing regulation and in deciding which authority is responsible for them. For example, if a cryptoasset is deemed to be a security, its distribution and secondary trading would be under the provisions of the securities law in place. Hence, the applicability of securities law would trigger the enforcement of a number of regulatory requirements and obligations. Conversely, trading of cryptoassets used as payment tokens or service tokens would not be regulated under existing laws.

Table 1: Overview of major regulatory cryptoasset classification frameworks

Who is in charge?

Different types of authorities are playing a role in the emerging cryptoasset regulation at different levels, from supranational and intergovernmental, to domestic and national levels, with also a growing role for self-regulatory initiatives from the industry.

Given the global nature of cryptoassets and especially global stablecoins, it is not surprising that many international organisations and intergovernmental authorities have been especially proactive in engaging with the topic. The main objectives of international organisations and intergovernmental authorities is to promote common standards across jurisdictions or “regulatory harmonisation”, in a number of areas. Among others:

- The IMF and the World Bank have proposed the Bali Fintech Agenda (BFA), with the aim to discuss the high-level issues that should be considered in their policy discussions. This agenda has regulatory and supervisory considerations for the monitoring, regulation, and supervision of crypto assets.

- The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) issued a “statement on cryptoassets” (March 2019), and a consultative document (December 2019) to highlight the landscape of risks for banks and to provide a view on prudential measures related to banks’ exposures to cryptoassets.

- The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) warned about the risks of cryptoasset offerings (ICOs) in January 2018 and created a network for its members to exchange information. It also has a standing fintech network in charge of keeping track of fintech developments and identifying policy needs.

- The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), who develop cooperation on policies to combat money laundering, adjusted its recommendations at the end of 2018 to explicitly clarify that they should apply to cryptoasset and related services.

In the case of the European Union (EU) at supranational level, their directives must be Incorporated into domestic laws. For example, the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (5AMLD) contained provisions for cryptoasset activities, which EU member states had to integrate into their domestic laws by January 2020. Other European initiatives have not been legally binding, such as the cryptoasset guidance published by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and the report published by the European Banking Authority (EBA). These two initiatives emphasised the need of a level playing field among EU member states and solicited EU institutions to consider EU-wide regulation on cryptoassets.

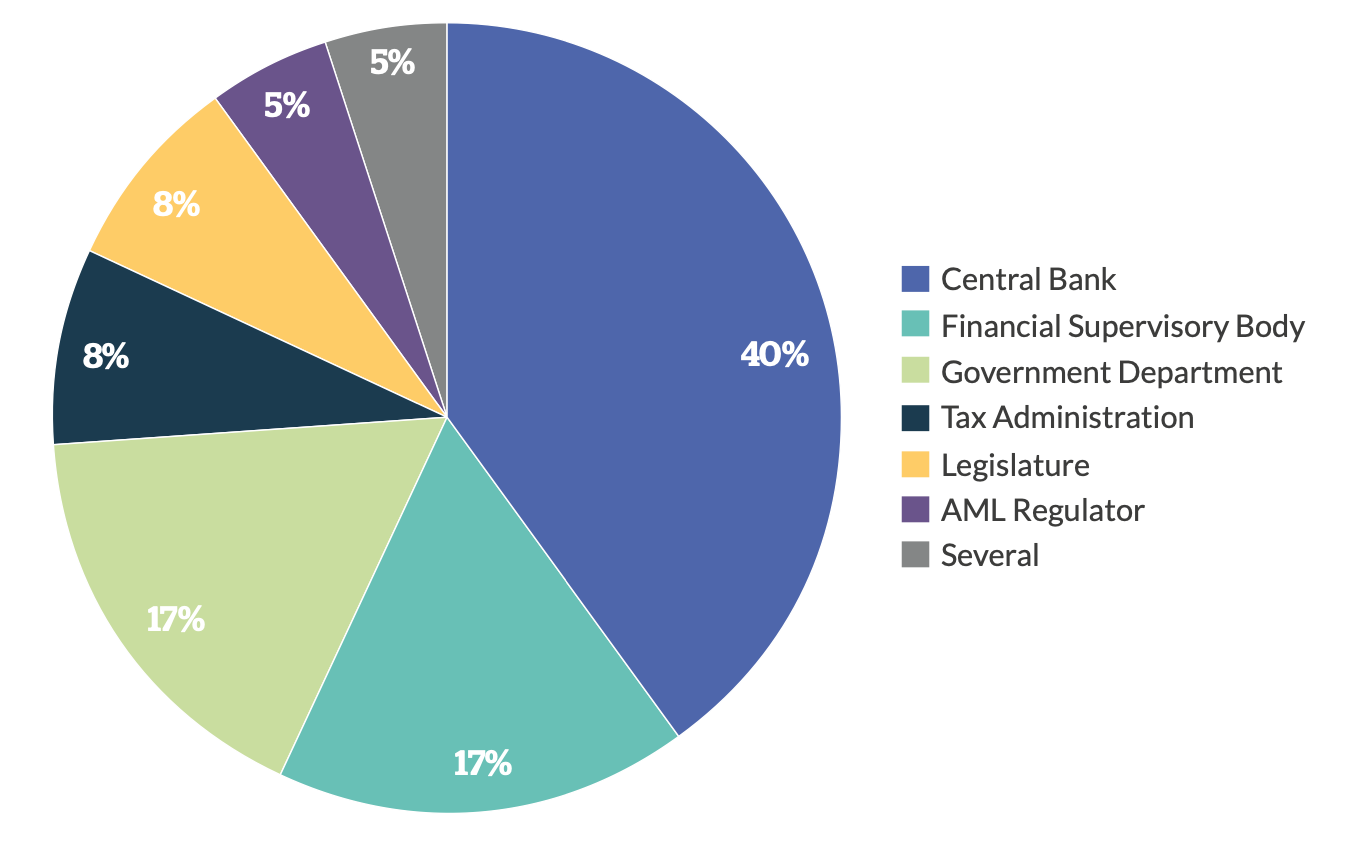

At the domestic level, initiatives on cryptoasset activities have been taken by a heterogenous number of public authorities, representing all three branches of the state – legislative, executive, and judiciary. The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (2020) suggests that central banks have generally been the generally the first type of authority to intervene, usually with statements (40% of the cases), followed by branches of the Government as the Ministry of Finance (17%), and financial supervisory bodies (17%).

Figure 2: Breakdown of classification of regulatory authorities that first issued an official statement on cryptoassets in their respective jurisdiction

In most of the jurisdictions, national regulators have issued some form of guidance or published warnings on cryptoassets and related activities. These “soft” interventions usually happen in the absence of “hard” legislative actions (e.g. USA, Switzerland). A very limited number of countries have adopted or enacted specific laws on cryptoassets (e.g. Malta, Bermuda).

One very apparent feature of the legal discussion on cryptoassets is that, in the absence of specific regulation, the legal perimeter under which they fall is still uncertain and likely to fall within the remit of several regulators. For example, in Australia, four regulators have responsibilities on securities and financial market stability. Such overlap can cause uncertainty for investors, and potential gaps in the regularly action taken. To try and alleviate to this situation, several countries have established working groups and consultation frameworks across regulators. For example, in the UK, the “Cryptoasset Taskforce” allows for discussions among the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the Bank of England (BoE), and Her Majesty’s Treasury.

Courts too have been active in defining the new legal perimeter by ruling on legal aspects of cryptoassets. This happens on the back of legal actions, and via the interpretation of the existing laws to the new cryptoasset activities, or by ruling on the legality of the regulators’ enforcement actions. For example, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled on whether banks have the right to deny bank accounts to cryptoasset companies, ruling in favour of the cryptocurrency exchange Bits of Gold and against an Israeli bank.5 In Germany, the highest court for the federal city state of Berlin recently ruled against the federal German financial regulator (BaFIN) in a criminal trial concerning an unauthorised Bitcoin exchange, by deciding that trading in bitcoins did not require authorisation from the BaFin.6 The decision was motivated by the finding that Bitcoin is not a financial instrument, nor a unit of account.

How is the regulation emerging?

To date, regulatory responses have mainly (but not exclusively) concerned the creation (ICOs) and trade of cryptoasset, and have come in four forms:4

- Application of existing regulations to cryptoasset activities by using “clarifications” on the applicability of extant laws and regulations. This has happened for example when governments have issued guidance on the applicability of securities laws or banking regulations to cryptoassets. For example, the Australian government has issued an information sheet (INFO 225) on ICOs and cryptocurrencies.

- Amendment of existing laws or regulations to include one or more cryptoasset activities (retrofitted regulation). This allows for an expansion of the scope of an existing regulation to explicitly cover certain cryptoasset activities. For example, Estonia has amended of the Money Laundering Act and Terrorism Financing Prevention Act to cover cryptoasset exchanges and wallets.

- Creation of bespoke regulation to regulate cryptoassets activities via new laws. This is the case of Malta’s Virtual Financial Assets Act.

- Creation of a specific bespoke regulatory regime for a larger set of activities (usually Fintech) that encompasses cryptoasset activities. This is the case of the Law to Regulate Financial Technology Institutions in Mexico.

Conclusions

Regulators in both developed and developing economies are getting to grips with the regulatory challenges raised by cryptoassets, in the effort to balance the benefits of innovation with other regulatory objectives such as financial stability and consumer and investor protection. The fast-moving pace of fintech innovation has challenged existing regulations and stimulated regulatory debate on how to develop sound legal frameworks to contain risks, while supporting healthy innovation and building trust.

Bibliography

Houben, R., Snyers, A., Crypto-assets (2020) – Key developments, regulatory concerns and responses, Study for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament, Luxembourg.

Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance - Apolline Blandin, Ann Sofie Cloots, Hatim Hussain, Michel Rauchs, Rasheed Saleuddin, Jason Grant Allen, Katherine Cloud, and Bryan Zhang - (2019), “Global Cryptoasset Regulatory Landscape Study”, Cambridge Judge Business School

The Law Library of Congress (2018) Regulation of Cryptocurrency Around the World. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/cryptocurrency/cryptocurrency-world-survey.pdf

The Law Library of Congress (2014) Regulation of Bitcoin in Selected Jurisdictions. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/bitcoin-survey/regulation-of-bitcoin.pdf

Cuervo, Cristina, Anastasiia Morozova, Nobuyasu Sugimoto (2019), “Regulation of crypto assets”, FinTech notes, International Monetary Fund https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fintech-notes/Issues/2020/01/09/Regulation-of-Crypto-Assets-48810

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2019) “Designing a prudential treatment for cryptoassets”, Discussion paper https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d490.htm

Comments received on the "Designing a prudential treatment for crypto-assets" https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/comments/d490/overview.htm

Footnotes

1 As for example the buying of illegal goods and services in darknet marketplaces, money laundering, evasion of capital controls, payments in ransomware attacks and thefts.

2 The report focusses on 23 selected jurisdictions: Abu Dhabi, Australia, Bermuda, Canada, China, the European Union, Estonia, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Hong Kong, India, Israel, Japan, Malta, Mexico, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, Switzerland, Thailand, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States of America (USA). Additional data for a total of 40 jurisdictions is obtained from The Law Library of Congress (2018).

3 In 1946, the Supreme Court decision on the case “SEC vs Howey” created the basis for the commonly applied Howey Test which is used to determine whether a transaction is an investment contract or not. A transaction will be deemed to be an investment contract if it fulfils the following criteria: (1) It is an investment of money; (2) The investment is in a common enterprise; (3) There is an expectation of profit either from the work of the promoters or the third party. Federal courts have accepted the definition of “common enterprise” as an enterprise by which the investors pool in their money and assets to invest in a project.

4 Most regulators have favoured an activity-based approach (i.e. regulation applicable to a specific type of cryptoasset activity) rather than an entity-based approach (i.e. regulation that applies to a particular type of company or entity).

5 See, for example, https://www.coindesk.com/crypto-exchange-bits-of-gold-wins-supreme-court-battle-over-bank-block

6 See, for example, https://www.ico.li/german-court-ruling-against-bafin/