The rapid technological and financial innovation brought by cryptocurrencies has prompted central banks across the world to consider the creation of sovereign digital currencies (BIS, 2018). Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) would be new digital forms of money provided by central banks to the public, valid as legal tender for all public and private transactions. The creation of CBDCs would be supported by a new payments infrastructure on which digital payments would be made.

Most central banks do not consider cryptocurrencies that are privately issued, such as Bitcoin, to be able to perform the same functions of money. Their high volatility does not seem to be compatible with the characteristic of stores of value, while their low acceptance currently implies that that they are not means of exchange or units of account (see, for example, ECB, 2015 and Carney, 2018). However, the creation of stablecoins, which are thought to provide stability of value via asset backing, as for example Facebook’s proposition of Libra, has jolted central banks and regulators into action.

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), has announced that it is “progressing smoothly” with its plan to develop a digital currency. The Bank of England has also been an early mover in the discussion surrounding the introduction of CBDCs (see Bank of England, 2020), in addition to the Bank of Canada, the Central Bank of Uruguay and the Swedish Riksbank. Also, the European Central Bank (ECB), while not officially engaged in the testing of a CBDC, has been active in the debate.

What is a Central Bank Digital Currency?

Currently, businesses and consumers have access to two (main) forms of money: banknotes and commercial bank money (electronic bank deposits). Only banks and some financial institutions have electronic accounts held directly at the central bank, in the form of reserves.

Differently from banknotes and similarly to reserves, CBDCs are purely digital and held on the central bank balance sheet. Differently from reserves and similarly to banknotes, CBDCs are fungible for the wider public. This is why CBDCs are often referred to as ‘central bank reserves for all’.

Two forms of CBDCs are possible:

- A retail CBDC, that is a consumer-facing payment instrument for retail transactions;

- A wholesale CBDC, i.e. a restricted-access, digital settlement instrument for wholesale payment applications only (i.e. for financial institutions).

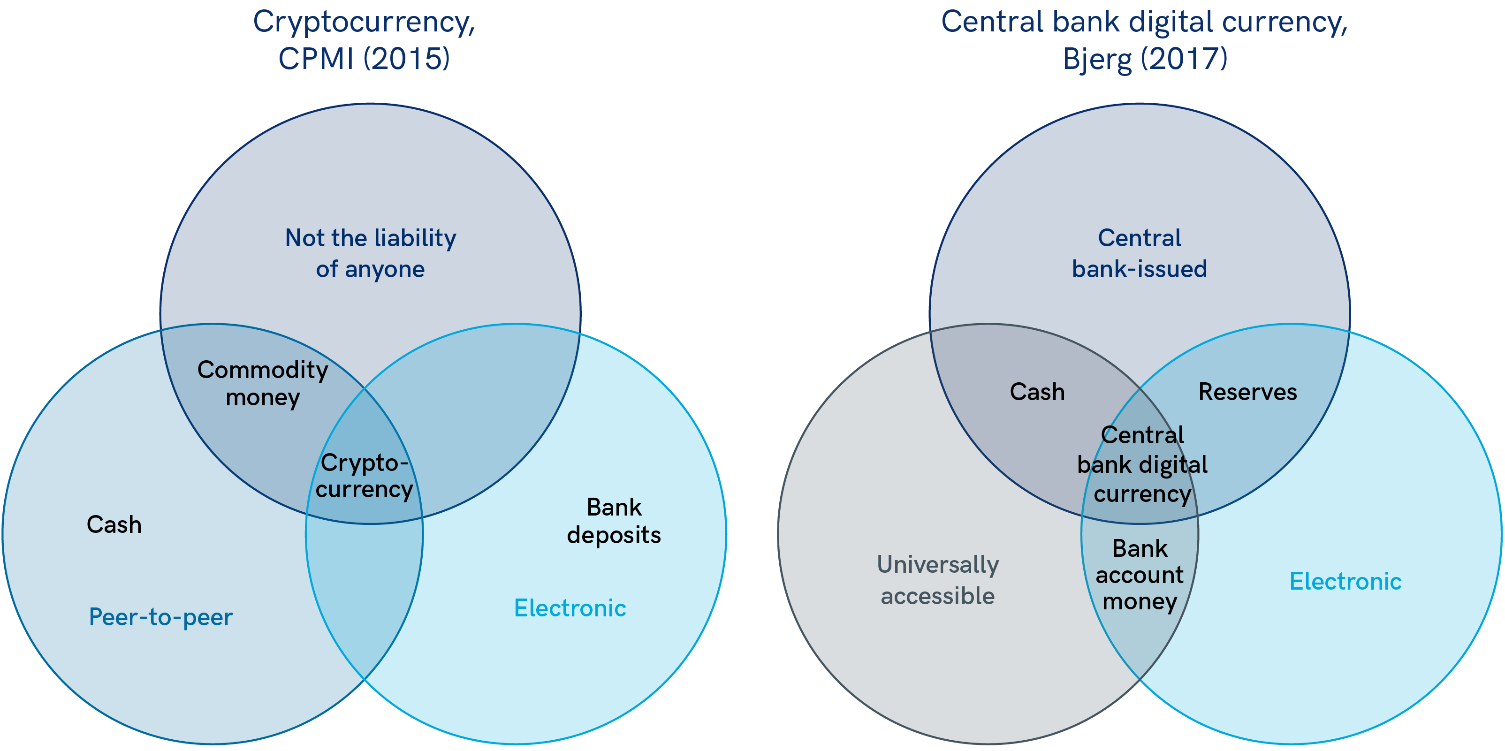

Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the different types of money and their properties. This figure differentiates between publicly and privately issued digital currencies. A retail CDBC is defined at the intersection of the three properties of being issued by a central bank, universally accessible and electronic.

From the point of view of central banks, the introduction of retail CBDCs has many potential advantages.1 Among others, they can:

- Restore the role of money as a public good

- Reduce the risks entailed by new forms of private money creation

- Guarantee financial stability against the potential credit risk of privately issued monies and commercial deposits

- Guarantee a resilient and efficient payment system

- Guarantee the uniformity of the payment system in a currency area

Figure 1: Types of Money

An important design choice that will determine the economic impact of CBDCs is whether they will be:

- unremunerated (non‑interest bearing) like banknotes; or

- remunerated (interest bearing), as central bank reserves and bank deposits

With a non‑interest bearing CBDC, households and business would have a smaller economic incentive to move away from bank deposits. This, in turn, would reduce the impact on the banking system’s ability to provide credit. However, from the point of view of a central bank, by offering a near zero cost option to hold liquidity, it would reduce the extent to which it could reduce interest rates into below zero, limiting the effectiveness of one of their key policy tools.

Conversely, an interest bearing CBDC would produce a larger shift out of bank deposits that, in turn, could entail negative implications on the banking system, monetary policy and financial stability. However, the rate paid on an interest bearing CBDC – potentially positive or negative – would give the central bank an additional monetary policy instrument, and allow for faster and more direct transmission of monetary policy (Bordo and Levin, 2019).

A second important design choice concerns the technology used. Cryptocurrencies and digital currencies are associated with Distributed Ledger Technology, the innovation brought about by Bitcoin. However, central banks will have to decide on the degree of centralisation of the technology adopted in providing CBDCs. This, in turn, will have implications on the type of private-public synergies allowed in the creation of the payment ecosystem. Crucially, the degree of efficiency, resilience and level of privacy of the system will be determined by the type of technology adopted – centralised vs decentralised – and the level of involvement of private enterprises in the creation of customer-facing payment gateways. Most likely, the level of privacy guaranteed by CBDCs would likely be lower as compared to cash or cryptocurrencies.2

Economic Implications of CBDCs

The introduction of a CBDC could have large and significant implications for the banking system, monetary policy and financial stability.

Three of the main questions raised are:

- Whether a CBDC could squeeze profits that banks generate by creating deposits

- Whether this could in turn choke investment

- Whether a CBDC could undermine financial stability by eroding bank assets and make bank runs more likely

To understand what could happen, it is important to observe that commercial bank deposits are an essential part of the banking sector’s funding. The creation of CBDCs, could cause ‘disintermediation’, with a shift away from banks’ deposits and a downsizing of banks’ balance sheets (see, for example Broadbent, 2016). This would increase the cost of funding for commercial banks that would have to either pay higher interest rate on deposits or seek to replace lost deposit funding with alternatives, such as longer‑term deposits or wholesale funding. If an increase in the efficiency of the financial sector does not materialise, this could imply an increase the cost, and thus lower the volume, of bank lending.

Some of the implications of the introduction of CBDCs are yet to be fully clarified. However, Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019), in a recent work, argue that in equilibrium CBDCs will reinforce financial stability and be a positive development overall. The main argument is that CBDC would fund new investments, while banks could be compensated if the welfare implications of their loss of their role were to be judged undesirable. They also argue that bank runs would become less probable. With CBDCs, central banks could become the largest depositors and the least likely to lose the trust of its customers. Also, central banks can gain an informational advantage and engage more quickly as lenders of last resort. These two factors also make bank run less likely, in the first place.

Conclusions

The emergence of cryptocurrencies and stablecoins originally posed a challenge to the role of central banks and national currencies. The proposal of a central bank digital currency is an attempt to address this, by envisaging the creation of a form of central bank digital reserve, universally available to both businesses and consumers. The introduction of CBDCs seems to be nearing at fast speed and could have important consequences for the banking system, monetary policy and financial stability. Some of these consequences are yet to be fully understood by policymakers and academics.

Bibliography

Broadbent, Ben (2016), ‘Central banks and digital currencies’, speech given at London School of Economics on 2 March.

Carney, Mark (2018), ‘The Future of Money’, speech given to the inaugural Scottish Economics Conference on 2 March.

Bank of England (2020): ‘Central Bank Digital Currency. Opportunities, challenges and design’, Discussion Paper

Bordo Michael D. and Andrew T. Levin, A (2019), ‘Digital Cash: Principles and Practical Steps’, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 25455

Bank for International Settlements (2018), ‘Central Bank digital currencies’, Discussion Paper

Markus K Brunnermeier, Dirk Niepelt (2019), ‘Public versus private digital money: Macroeconomic (ir)relevance’,

https://voxeu.org/article/public-versus-private-digital-money-macroeconomic-irrelevance

Bech, Morten and Rodney Garratt (2017), ‘Central bank cryptocurrencies’, BIS Quarterly Review

European Central Bank (2015), ‘Virtual currency schemes – A further analysis’,

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/virtualcurrencyschemesen.pdf.

Footnotes

1 See Is Money a Public Good?: https://www.aaro.capital/Article?ID=3981d31a-7f37-4efa-bb83-84a2ed054fb7

2 The exact level of privacy depends on the technical design of the CBDC, with some designs allowing for a large level of privacy whilst still being compliant with regulation.