Central Bank Digital Currencies In Africa

Fintech has seen a substantial rise in adoption and innovation in Africa. Africa is now leading the way in the adoption of CBDCs. In this article we examine the potential benefits and challenges of the that may arise.

Introduction

The African fintech sector has been growing rapidly and has transformed the payment systems in the continent. Fintech companies have been leveraging mobile technology to create innovative digital payment systems and provided financial services to millions of previously unbanked individuals.1

Africa has been long a creative lab in fintech innovation. M-Pesa, the very first mobile payment system in Africa, was launched in Kenya in 2007. At the present Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for two-thirds of the mobile money transactions volume and more than half of the active users in the world (GSMA, 2022). More recently, banks and fintech firms have moved to experiment with new means of payment, such as cryptoassets and stablecoins.

Against this background, central banks in many African countries are now moving ahead of the rest of the world with new digital currencies. A recent survey of the BIS has reported that all the 19 central banks surveyed are active in Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) projects (Alberola and Mattei, 2021).

CBDCs are digital currencies issued by the central bank of a country or region. CBDCs are digital representations of a country's fiat currency, backed by the full faith and credit of the government. They are designed to be a safe, secure, and convenient means of payment that can be used by anyone with a smartphone or other internet-enabled device.

While most CBs are in the initial stage of research and assessment, Nigeria has moved ahead issuing the eNaira on 25th October 2021, the second retail CBDC in the world. Meanwhile, Ghana, Eswatini, and South Africa are already running pilot projects.

In this article, I will examine the potential adoption of CBDCs in Africa, including the potential benefits and challenges that may arise.

Potential Benefits of CDBC Adoption in Africa

Financial inclusion is possibly the leading benefit of the implementation of CDBC in Africa. According to the World Bank, around half of African adults (and up to 66% of adults in sub-Saharan Africa) are unbanked. A greater proportion than in any other region. This means that a large portion of society does not have any access to formal financial services such as savings accounts, credit, and insurance. They are fully dependent on a cash economy. CBDCs can potentially provide a means for unbanked individuals to access digital financial services, thereby increasing financial inclusion and reducing poverty.

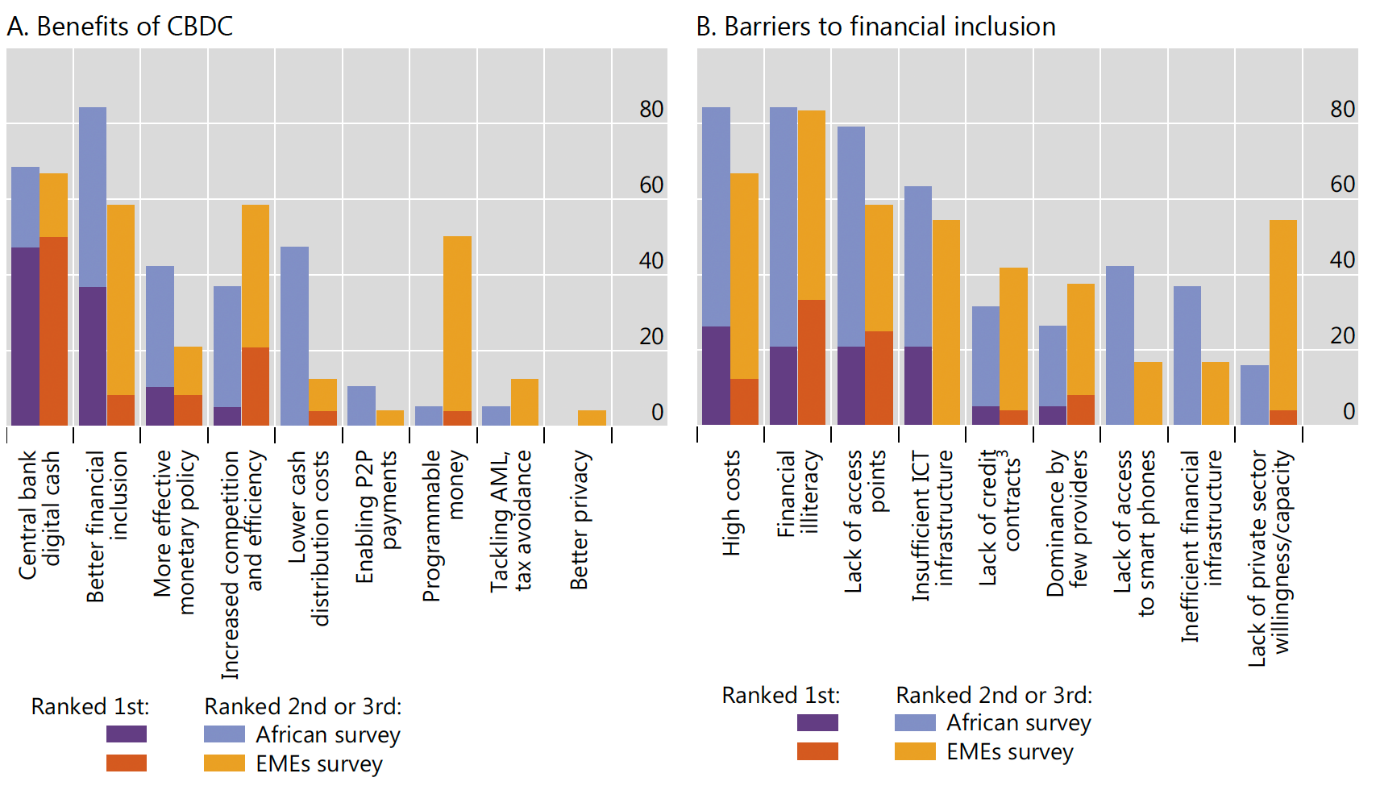

Indeed, the BIS survey reflects this reality and reports that the top motivations for CBDC issuance in Africa are (Figure 1):

• the provision of cash in digital form, and

• the promotion of financial inclusion.

As compared with other EMEs, financial inclusion is clearly a more pressing concern. Other motivations provided are:

• improving the effectiveness of monetary policy,

• increasing competition and reducing distribution costs of money.

Conversely, as compared to other EMEs, there is less emphasis on encouraging competition and having programmable money.

Figure 1 – What motivates the creation of CDBCs in Africa?

CBDCs in Africa can also improve quality of government by reducing corruption and money laundering and facilitate greater financial transparency and accountability. Because CBDC transactions are digital and recorded on a blockchain, they can be more easily tracked and monitored. This can make it more difficult for corrupt officials and criminals to launder money, but it raises concerns for privacy and government control.

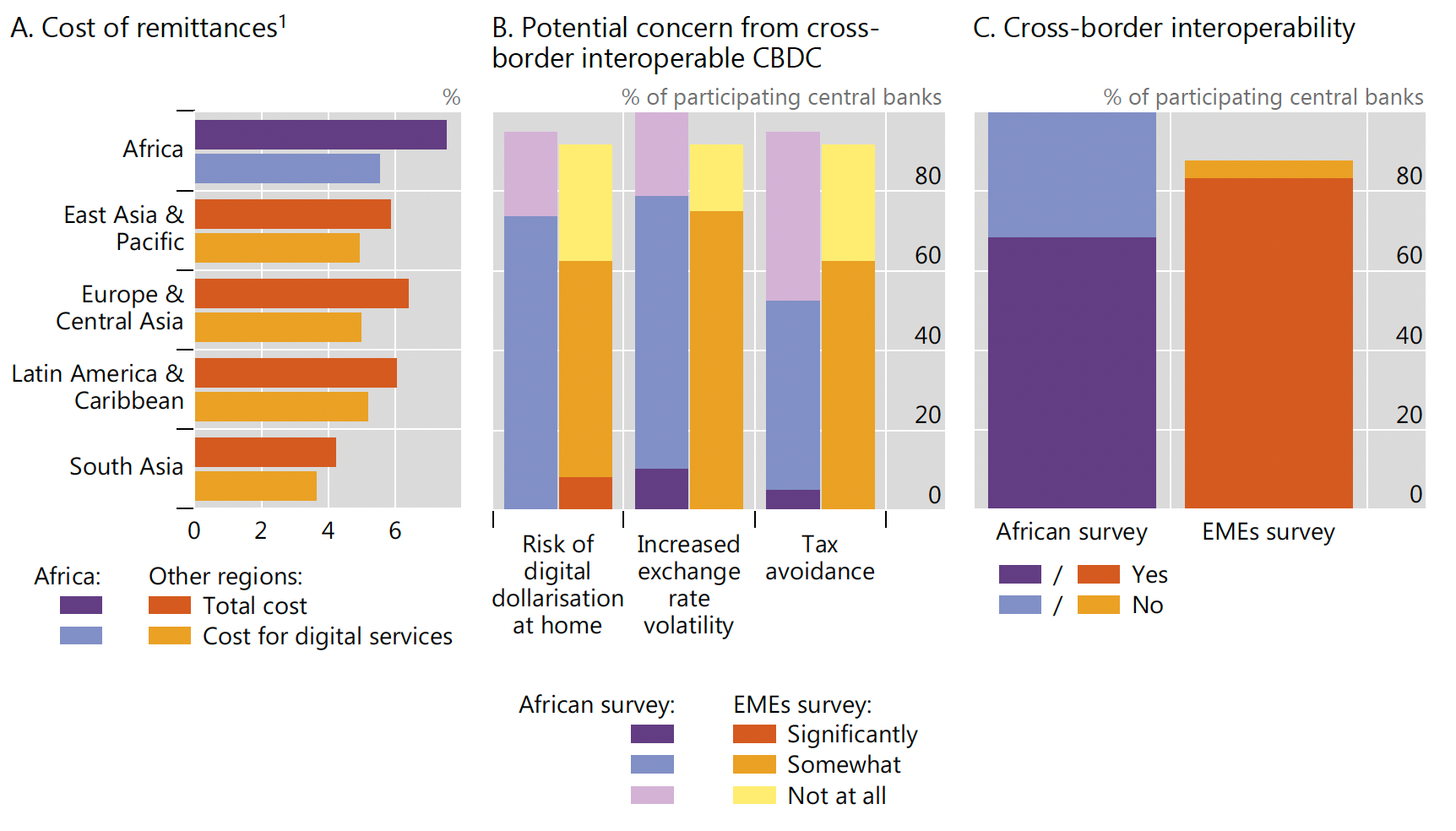

Figure 2 – Cross-border CBDCs

CBDC adoption has also the potential to reduce transaction costs especially across borders (Figure 2). An international system of CBDCs, connected by an mCBDC bridge could drastically increase the efficiency of cross-border transactions which are currently expensive, with high fees and long processing times. That would benefit many, including migrant workers transferring funds back home.2

In providing a local and efficient system for international transactions, CDBCs can also reduce reliance on foreign currencies. Many countries in Africa use the US dollar or euro for international transactions, which can expose businesses and consumers to exchange rates risk and make it difficult for businesses to plan and operate. A CBDC could provide a more stable and reliable currency for cross-border transactions within Africa, reducing reliance on foreign currencies.

Finally, CBDCs can provide greater monetary policy control for central banks. With CBDCs, central banks can monitor and control the money supply more effectively, which can help to stabilise the economy.

Challenges of CDBC Adoption in Africa

There are several challenges to CBDC adoption in Africa. Among others, a key one relates to infrastructure. Many countries in Africa do not have the necessary public infrastructure to support the universal adoption of CBDCs, such as reliable internet connectivity and widespread smartphone networks. For CBDCs to be successful, governments and private sector stakeholders will need to invest in infrastructure to support them.

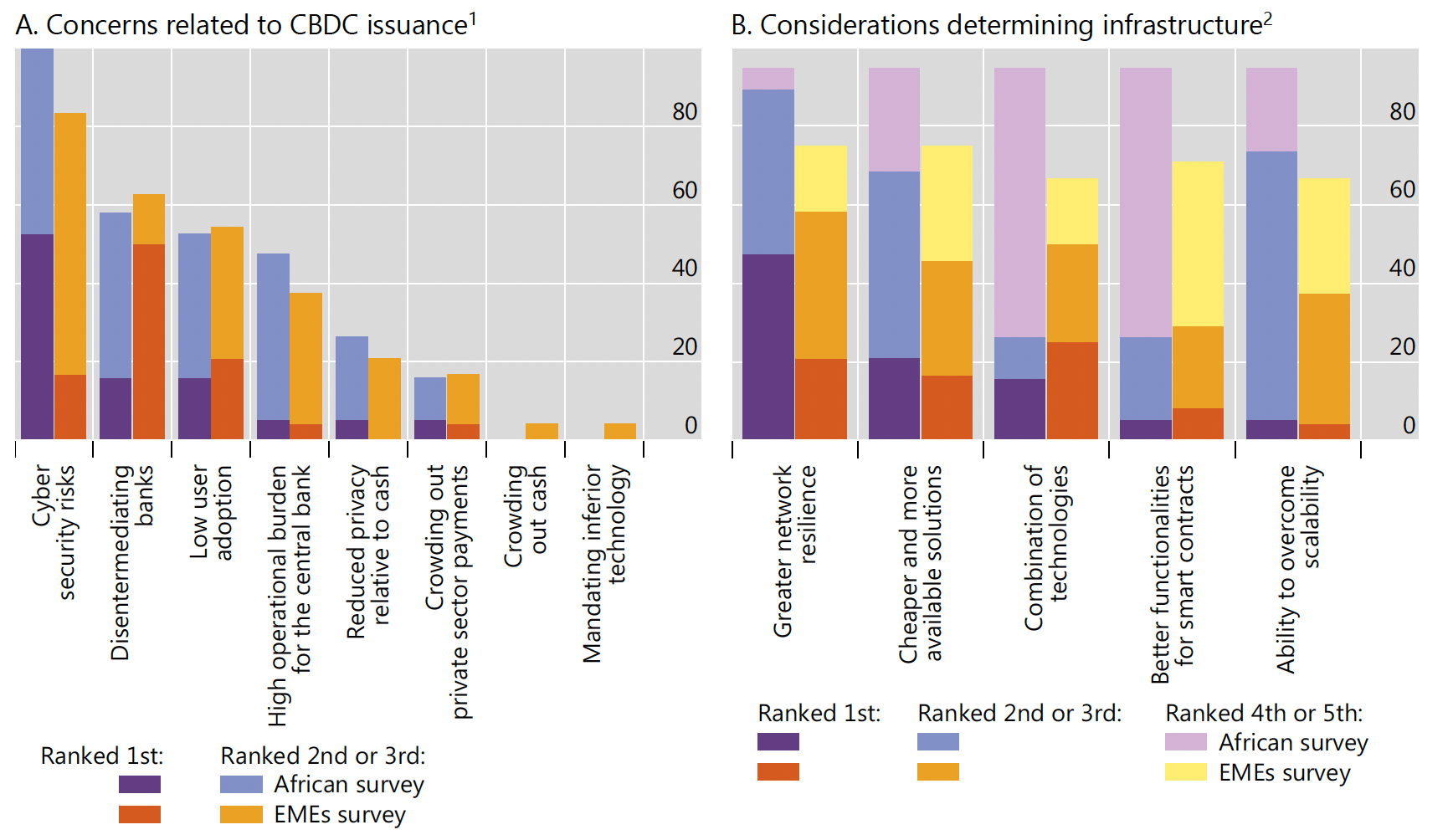

Figure 3 – Concerns related to CBDCs

From the point of view of central bankers, the main concerns related to CBDCs (Figure 3) are operational. Above all other worries, African central bankers put cyber security, followed by the burden for central banks of maintaining the system and its resilience and stability.

A successful cyber-attack on CBDCs could cause large damage and potentially destroy the reputation of the electronic currency for good. Such attacks operated on credit card systems, data on consumer credit profiles, and even central banks are not uncommon. A notorious case is the Bangladesh Bank cyber heist in 2016.

Low user adoption appears to be a concern to central banks. This is reported to be a particularly widespread concern in North Africa, where digital payments are not widely used. More generally, many people in Africa still prefer to use cash for transactions and may be hesitant to adopt new digital payment methods.

African central banks are also concerned by bank disintermediation, albeit to a lesser extent than other EME. If the CDBCs are perceived to be safer and more convenient than bank deposits (and especially if CDBCs are remunerated) this could dent banks’ businesses. Deposit disintermediation would force banks to rely on more expensive and less stable funding sources, and in turn reduce credit provision and raise loan rates.

These concerns can be alleviated with suitable design choices. In fact, the central banks working on the implementation of CDBCs have key decisions to make:

• The type of CBDC, either retail or wholesale, with the former accessible to the general public and the latter only available to select financial institutions.

• Domestic interoperability. It is generally accepted that the easier the transfer of funds among public and private payment platforms, the better.

• Degree of central bank involvement. This is a key decision on the type of architecture: a two-tier CBDC, with the central bank at the core, but private agents (banks and PSPs) interacting with users; or a direct system where the central bank also takes care of user-facing activities.

• Remuneration. This is potentially dangerous to disintermediation, as discussed. Only a small share of African central banks is considering this option.

• Limits on the quantities of CDBCs allowed to private institutions and consumers. This dimension has a bearing on disintermediation.

• Data governance. A majority of central banks are uncertain or do not see the need for a specific data governance policy. The BIS report notes that “this degree of uncertainty probably reflects the absence of a globally accepted standard on data governance, including for digital currencies”.

• Technology: distributed ledger (DLT) vs central ledger (CLT). Each option is seen by central bankers as having advantages and disadvantages.

CBDC Adoption in African Countries

The first Africa CBDC and the second in the world to appear is the Nigerian eNara.3 It is built upon a permissionless distributed ledger technology (DLT), with intermediaries making up nodes in the network. The system adopts a two-tier CBDC model.

The eNaira is issued by the CBN, which acts as the sole issuer and regulator of the digital currency. The CBN creates eNaira by purchasing Naira from authorized banks in exchange for newly created eNaira. Authorized financial institutions, such as banks and other licensed payment service providers, can distribute the eNaira. Users can acquire eNaira by either exchanging Naira for eNaira or by purchasing eNaira from authorized financial institutions. The digital currency can be used to conduct a wide range of transactions, such as payments for goods and services, remittances, and peer-to-peer transfers. Users can make eNaira transactions using their mobile phones or other electronic devices through authorized payment service providers.

The central bank issues the eNaira through the Digital Currency Management System (DCMS), while the participating financial institutions maintain eNaira Treasury Wallets on the DCMS. The Merchant Speed Wallets are used solely for receiving and making eNaira payments for goods and services, while the basic Speed Wallets are available for end users, typically households, to transact on the eNaira platform. The financial institutions also carry out onboarding of customers and AML/CFT controls. The eNaira uses advanced encryption technology to ensure that transactions are safe and secure. Additionally, the CBN monitors the eNaira network to prevent fraud and other illicit activities.

Several other countries in Africa have started working on CBDCs. In 2019, the Central Bank of Tunisia announced that it was exploring the possibility of launching a digital dinar. The Banks of Ghana and Eswatini have also announced that they are working at launching digital currencies.

In addition to these countries, the African Union (AU) has also expressed interest in a continent-wide digital currency. In 2019, the AU launched the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), which aims to facilitate cross-border payments and trade within Africa.

Conclusions

The adoption of CBDCs in Africa has the potential to be a game-changer for the continent's financial system. While there are many challenges to overcome, the potential benefits are significant, including increased financial inclusion, reduced transaction costs, and greater monetary policy control.

To achieve these benefits, it is important that governments, central banks, and private sector stakeholders work together to invest in infrastructure, cybersecurity, regulation, and education.

A key concern to address, especially in countries with a weaker institutional framework, is the potential impact of CBDCs on privacy and civil liberties. It is important that citizen groups, governments, and central banks work closely with legal experts to ensure that CBDCs are developed and implemented in a way that is consistent with privacy and the defence of civil rights.

Bibliography

Alberola, E., and Mattei, I. (2021). Central bank digital currencies in Africa. BIS Bulletin, No. 28, 1-8

https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap128.pdf

International Monetary Fund. (2020). Central Bank Digital Currencies: Opportunities, Risks and Challenges https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/04/16/Central-Bank-Digital-Currencies-Opportunities-Risks-and-Challenges-49335

SPA Ajibade (2022). An Overview of The Nigerian Central Bank Digital Currency

https://spaajibade.com/an-overview-of-the-nigerian-central-bank-digital-currency/

Bank of Ghana. (2021). Bank of Ghana to begin pilot testing digital currency

https://www.bog.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CBDC-Joint-Press-Release-BoG-GD-3.pdf

The Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS)

https://papss.com/media/in-the-media/the-pan-african-payments-and-settlement-system-papss/

GSMA. (2022). State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money

https://www.gsma.com/sotir/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/GSMA_State_of_the_Industry_2022_English.pdf

McKinsey & Company. (2022). Fintech in Africa: The end of the beginning

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/fintech-in-africa-the-end-of-the-beginning

McKinsey & Company. (2016). Digital finance for all: Powering inclusive growth in emerging economies

https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/employment-and-growth/how-digital-finance-could-boost-growth-in-emerging-economies

World Bank. (2021). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19

https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex

Footnotes

1 Mobile money is a type of digital payment system that allows consumers to send and receive money using a mobile device. Mobile money has become increasingly popular in Africa, where many people do not have access to traditional banking services. According to the GSMA, a trade association representing mobile network operators, there were over 160 million mobile money accounts in Africa as of 2020, with over $500 billion in transactions processed annually. Popular mobile services are M-Pesa, Orange Money, MTN Mobile Money, Airtel Money, and Tigo Cash.

2 OMFIF’s ‘Future of payments’ 2021 report indicated that global remittances to low- and middle-income countries amounted to $540bn in 2020. With over 200 million migrant workers across 40 countries sending money to a 800m people in 125 countries.

https://www.omfif.org/2022/11/cross-border-retail-cbdcs-can-help-financial-inclusion-for-migrants/

3 The governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, Godwin Emeiele, has declared that ‘Since the launch of this great initiative, the eNaira has reached 840,000 downloads, with about 270,000 active wallets comprising over 252,000 consumer wallets and 17,000 merchant wallets. In addition, the volume and value of transactions on the platform have been remarkable, reaching above 200,000 and ₦4bn[$9m], respectively.’

https://www.omfif.org/2023/01/one-year-later-enaira-as-a-force-for-financial-inclusion-and-digital-payments/

Disclaimer