The Challenges of Decentralised Finance

Decentralised Finance (DeFi) aims to provide a full range of financial services and products in a decentralised setting using smart contracts running on a distributed ledger, in a "trustless" and permissionless environment, removing intermediation and enhancing market efficiency.

Decentralised finance has been one of the fastest growing sectors within crypto, growing into a multi-billion-dollar industry, with up to around $200 billion locked in DeFi protocols as of February 2022.1

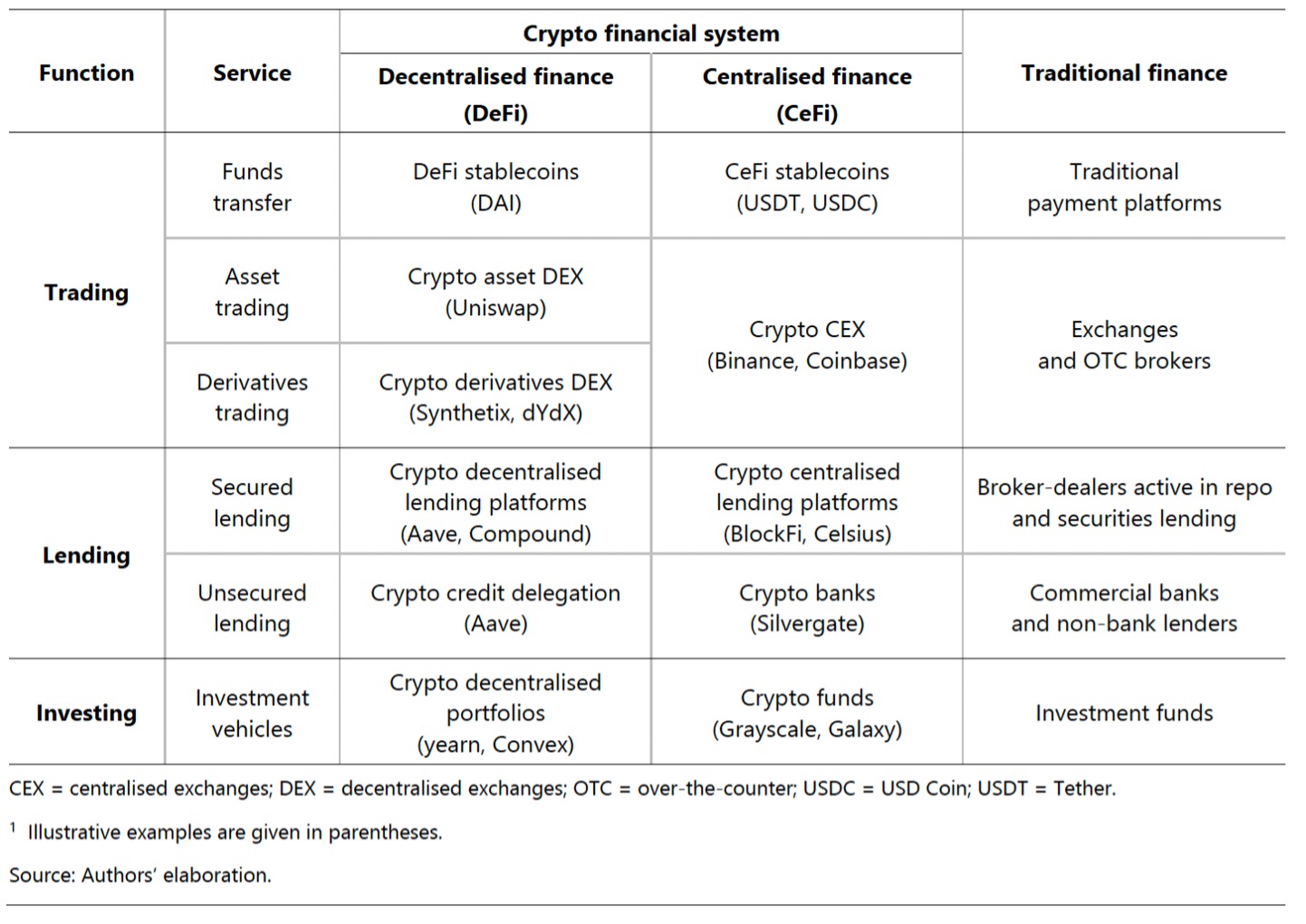

Figure 1 offers a table comparing traditional finance to DeFi and centralised finance (CeFi) in crypto markets. CeFi functions are similar to traditional intermediated finance and adopt centralised private records, for example, centralised crypto exchange platforms. Conversely, DeFi runs smart contracts based on decentralised applications (dApps) on distributed ledgers, that enact pre-determined financial contracts directly between participants. Smart contracts, or DeFi protocols, are generally open-source software.

Figure 1 – Crypto vs Traditional Finance

Despite DeFi's spectacular growth, a recent paper on the Bank of International Settlements’ Quarterly Review has offered a critical view of DeFi by labelling it “the decentralisation illusion” (Aramonte et al, 2021). The key passage in the paper reads:

[…] we argue that some form of centralisation is inevitable. As such, there is a “decentralisation illusion”. First and foremost, centralised governance is needed to take strategic and operational decisions. In addition, some features in DeFi, notably the consensus mechanism, favour a concentration of power.

In principle, DeFi has the potential to complement traditional financial activities. At present, however, it has few real economy uses and, for the most part, supports speculation and arbitrage across multiple cryptoassets. Given this self-contained nature, the potential for DeFi-driven disruptions in the broader financial system and the real economy seems limited for now.

The challenge, coming from a key institution in the global financial system (the “bank of central banks”), has stirred an intense debate and many reactions. In this article, we look into the arguments proposed, and in how critical and convincing they are.

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

The BIS article offers three key arguments. Let’s look at them in order.

Algorithm incompleteness. First, there is a theoretical argument coming from the economic literature on contracts:

[…] full decentralisation in DeFi is illusory. A key tenet of economic analysis is that enterprises are unable to devise contracts that cover all possible eventualities […]. Centralisation allows firms to deal with this “contract incompleteness” (Coase (1937) and Grossman and Hart (1986)). In DeFi, the equivalent concept is “algorithm incompleteness”, whereby it is impossible to write code spelling out what actions to take in all contingencies.

This is a broad sweep argument. The pioneers of the incomplete contracting paradigm – Grossman and Hart (1986), Hart and Moore (1990), and Hart (1995) – argued that contracts cannot specify what should be done in every possible future scenario, since they may escape people's ability to fully identify them, given the extremely large number of possible (even if unlikely) situations which could happen. This implies that parties may wish to renegotiate in the future to enhance the welfare of both parties. The implication is that a contract could or should not be fully automated with a pre-programmed and immutable protocol, since there will exist some future states of the world where renegotiation would be desired by both contracting parties.

This is an argument about immutable self-executed protocols as being welfare dominated by (worse than) flexible, renegotiable contracts between parties. Yet the argument abstracts from the role of intermediation in financial markets, often thought to be needed to help matching parties with different desired maturity and risk profile to their exposure, or to overcome information asymmetries in the market.

What happens to the argument when, due to market frictions, one has to introduce an “intermediator” into the picture? The question becomes, whether the presence of financial intermediation – as in traditional finance – that can either reduce or induce inefficiency has, on balance, a lower welfare cost to consumers and investors than the cost that even a complex and well specified automated contract may impose in some future state of the economy. This is the real-world challenge against which DeFi has to measure itself: to show that its outcomes are in “most states” of the world superior to those of intermediated and centralised, but flexible systems.

A related argument concerns the balance between welfare costs and inefficiencies due to centralisation and market power, as compared to the inefficiency due to decentralisation. In the context of public ledgers, many (often all) network participants are involved in verifying the correct execution of contracts. Thus, smart contracts are computationally very inefficient compared with traditional centralised ledgers and lack flexible inbuilt mechanisms to re-negotiate undertakings.

However, the BIS paper’s argument on contract incompleteness has a narrow focus on purely automated contracts. While DeFi is commonly defined as completely automated smart contracts, the broader world of Decentralised Finance potentially extends to many protocols characterised by forms of progressive decentralisation – from decentralised vetting of borrowers and credit delegation to cooling-off periods, where before contract execution, human intervention can happen to correct mistakes and prevent frauds. This is at present a largely unexplored space.

Stealth re-centralisation. The second argument comes with an interesting observation about governance on distributed ledgers

[…] certain features of DeFi blockchains favour the concentration of decision power in the hands of large coin-holders.

Concentration can facilitate collusion and limit blockchain viability. It raises the risk that a small number of large validators can gain enough power to alter the blockchain for financial gain.

This is an important point. The mechanisms by which validation on distributed ledgers happen can over time allow fewer validators to gain dominant power over the ledger, appropriating rewards and potentially re-centralising the system.

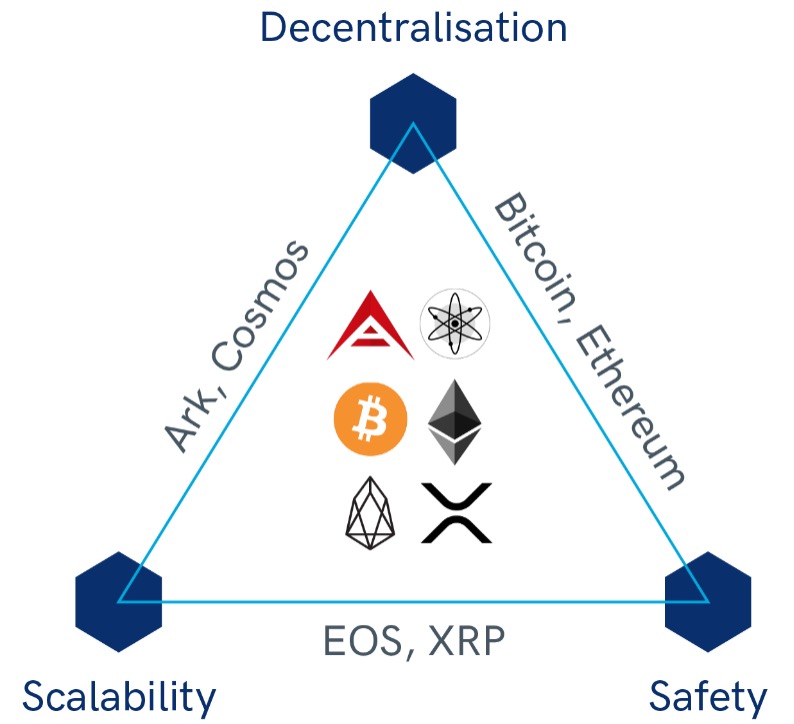

This is probably a general question about the crypto space – how centralised are decentralised protocols at present and how will they evolve in the future? As observed in the crypto community, distributed ledger networks, while claiming to be full decentralised, have varying levels of centralisation at their core.2 Some of this is due to the development stage of projects, which are easier to launch in a centralised manner and to progress towards decentralisation as it becomes established. Some of these elements of centralisation are due to the so-called scalability trilemma. It is very difficult (if not impossible) to achieve the following three desirable objectives simultaneously: security, scalability, and decentralisation.

Figure 2: Impossibility Triangle for Distributed Ledger Technology

However, this is less than a definitive statement about what will happen and more of an open question about robust system design and the different potential paths that the crypto world can choose or be corralled onto.

DeFi vulnerabilities. Third comes an argument about risks in DeFi and how they could affect the system:

While DeFi is still at a nascent stage, it offers services that are similar to those provided by traditional finance and suffers from familiar vulnerabilities. The basic mechanisms giving rise to these vulnerabilities – leverage, liquidity mismatches and their interaction through profit-seeking and risk-management practices – are all well known from the established financial system.

DeFi’s vulnerabilities are severe because of high leverage, liquidity mismatches, built-in interconnectedness and the lack of shock-absorbing capacity.

This is very much in the remits of the BIS and the bank is right in pointing to the weakness and risks building up in the crypto world and DeFi.

There are two elements to this argument. First, DeFi suffers from the same type of vulnerabilities of traditional finance. Second, for DeFi these vulnerabilities may bite harder due to the automated nature of these services, that can lack backstops and points of human intervention.

To understand what can be wrong, one can look at the flash crashes that have been experienced by cryptoassets. Some of these flash crashes have been explained by large sell orders, that cause a large drop of price, and that in turn triggers a cascade of automatic margin calls and stop loss orders set by traders, which cause a rapid and sudden price drop. These kind of market dynamics in a system without sufficient buffers and potential space for external intervention – as for example the circuit breakers used in traditional markets – can have large domino effects and contagion.

Contagion is not alien to traditional finance, that has seen several such episodes. However, while the traditional financial system today is highly regulated and has public and private shock absorbers, DeFi relies exclusively on the independently chosen collateral, which may not be sufficient to absorb shocks, especially If there is contagion in crypto or across the economy.

On balance, this argument, rather than a definitive indictment of DeFi, points to an important challenge for both DeFi proposers and regulators. The DeFi space is still a nascent market which will need to find the right balance between self-chosen governance to reduce risks and external regulation.

Conclusion

DeFi was created to enable automated peer-to-peer lending and borrowing in the crypto space. It has expanded to an array of services and to the promise of complementing against traditional financial services and even transforming them. The BIS article rightly highlights some important challenges and considerations which DeFi must overcome – service efficiency and flexibility, decentralised governance, backstops and regulatory framework, not to mention cybersecurity.

While many in the crypto space may be tempted to simply dismiss the BIS view as coming from an outdated financial system mindset, they would be wise to evaluate the criticism seriously. The efficiency of decentralised automated protocols must be proved and cannot be assumed. There is much to gain from operational and regulatory frameworks that protect investors and preserve the integrity and stability of financial markets.

Bibliography

Aramonte, Sirio, Wenqian Huang and Andreas Schrimpf, “DeFi risks and the decentralisation illusion,” BIS Quarterly Review, December 2021

www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d187.pdf

Schar, Fabian, “Decentralized Finance: On Blockchain- and Smart Contract-Based Financial Markets,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Second Quarter 2021, 103(2), pp. 153-74.

Footnotes

1 The size of this market is not straightforward to measure. The commonly adopted measure is the value of capital that is locked in DeFi-related smart contracts. It is important to stress that these are not transaction volume or market cap numbers, the value refers to reserves locked in various smart contracts. According to DappRadar, there were over 655,000 daily unique active wallets across all chains in the fourth quarter of 2021. See The Block, “Stablecoin supply grew by 388% this year, driven by DeFi and derivatives” by Frank Chaparro. According to Coinbase, in April 2021, many analysts were looking for a $100 billion valuation, while CoinGecko calculated a total market capitalization of $128 billion for decentralized finance (DeFi). Instead, according to data presented by Defillama, the DeFi market was at around $200bn in February 2022.

https://www.theblockcrypto.com/linked/128027/stablecoin-supply-grew-by-388-this-year-driven-by-defi-and-derivatives

https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2021/04/29/defi-is-now-a-100b-sector/

https://www.financialmirror.com/2021/09/29/defi-market-grows-335-to-85-bln

2 See, for example, How Decentralized Are Decentralized Networks? By Werner Vermaak on coinmarketcap

https://coinmarketcap.com/alexandria/article/how-decentralized-are-decentralized-networks

3 See, for example, “The fragility of decentralised trustless socio-technical systems” by Manlio De Domenico and Andrea Baronchelli on EPJ Data Science volume 8, Article number: 2 (2019)

https://epjdatascience.springeropen.com/articles/10.1140/epjds/s13688-018-0180-6