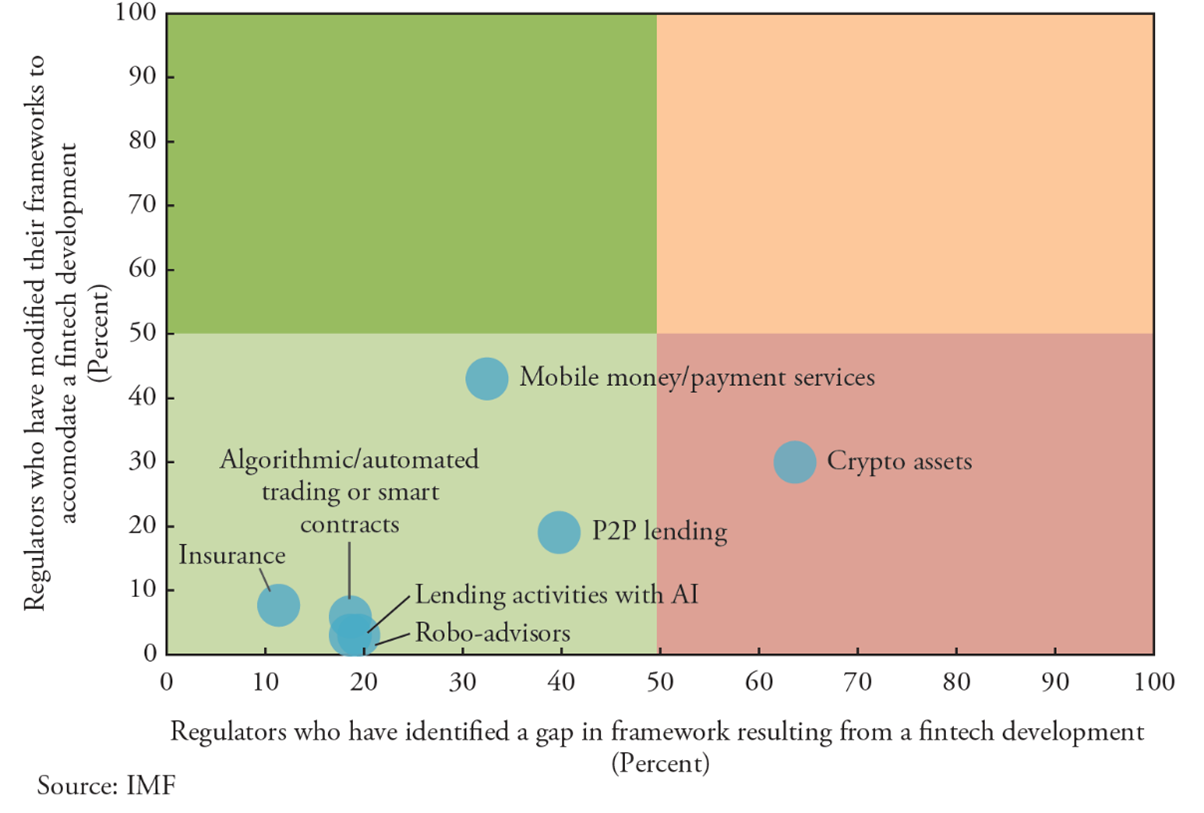

Regulators in several jurisdictions, and also at the supranational level, have been working on the creation of new legal frameworks for the Fintech sector and specifically for crypto finance activities. So far, very few have managed to implement comprehensive norms, while others are still in the early stages of proposing laws. A survey conducted by the IMF (2019) on Fintech regulation found that regulators identified cryptoassets as the main gap (64 percent) in the area, with only 30 percent having addressed it (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: A self-assessment of the completeness of Fintech regulation

The regulatory landscape is evolving quickly. Many observers consider 2020 as the pivotal year for crypto regulation, despite policy concerns being determined by the COVID pandemic and looming economic recession.

In this note, we survey the emerging regulation on cryptoassets and highlight some interesting case studies.

Regulated Activities and Enforcement

Mining is largely unregulated across jurisdictions. The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (2020) found that 45% of jurisdictions consider mining activities outside the scope of their regulatory perimeter, whereas 36% do not mention mining activities at all in their guidance. As an exception, the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) in Germany considers that mining pools offering shares (proceeds from mined cryptoassets in exchange for computing power) should obtain written authorisation to operate.

Intermediated activities that include distribution, exchange, storage, and payments are generally under some regulation. Most regulators have clearly established the distinction between cryptoassets bearing the features of security and other types of cryptoassets (see Regulation in the Crypto Space). When a cryptoasset qualifies as a security, distribution and secondary trading market activities automatically fall under the scope of securities law, whereas this is not necessarily the case for cryptoasset storage or payment services. The US SEC on the other hand, has put serious effort in enforcing securities regulation for ICOs and tokens classified as securities, setting a standard around the world. Also, the Monetary Authority in Singapore has issued a number of strong warnings to cryptoasset exchanges and ICO issuers.

For cryptoassets that do not qualify as securities, only some jurisdictions have developed a bespoke regulatory response. The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance found that 45% of jurisdictions have developed bespoke regulation for exchange activities, 36% for storage activities, and 27% for payment and distribution activities. In some cases, regulation has been brought forward by amending AML regulations to force compliance with their mandates.

Enforcement actions on exchange activities have taken place in Japan where, following a hack that caused severe losses at a cryptoasset exchange, the FSA mandated a review of risk management policies. In South Korea, the Korea Communication Commission (KCC) issued fines on cryptoasset exchanges for poor personal data protection practices.

Only a small number of jurisdictions have taken a draconian approach by prohibiting the distribution and the exchange of cryptoassets. In most of the cases, regulation is only banning some of the activities. For example:

- The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) prohibits the dealing in cryptoassets by regulated financial entities, but cryptoasset trading through other channels is still permitted. According to Bloomberg, India is planning to introduce a new law to tighten the ban in the country.1

- The Chinese regulatory ban only applies to cryptoasset-to-fiat exchange activities but not to cryptoasset-to-cryptoasset exchange activities.

A fast-moving regulatory landscape

Most regulators have acknowledged the potential of DLT and cryptoassets to reshape the financial and payment services, and ultimately provide value to consumers and investors. The developments over the last year highlights the global trend across jurisdictions to create new regulation for cryptoassets and provide certainty to consumers. Some notable cases in the advanced economies are:

- European Union. In September 2020, the European Commission (EC) presented a draft legislation on Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) as part of its broader Digital Finance Package.2 The MiCA regulation would provide a common regulatory framework across the single market to support the development of the cryptoasset market, the transition of traditional financial assets to tokenization, and the generalisation of distributed ledger technology (DLT) in the financial services sector. The draft MiCA defines three categories of cryptoassets: (i) utility token cryptocurrencies, (ii) single currency stablecoins, and (iii) complex “asset-referenced” stablecoins. Complex asset-referenced stablecoins of systemic scale will be overseen by the European Banking Authority (EBA). National regulators will have oversight over smaller initiatives, but might need to consult the national central bank, ESMA, the ECB and the EBA. For simpler stablecoins, MiCA recognizes that these have similar functions to e-money (as defined under the existing Electronic Money Directive (EMD) and hence would be brought under the same provisions. Besides the MiCA initiative, all EU countries were required to implement the 5th EU anti-money laundering Directive (5AMLD) in January 2020, which brought cryptoasset exchanges and custodial wallet providers under AML obligations.3

- France. The French Government has expressed its willingness to provide crypto businesses with a supportive regulatory framework. France’s PACTE Law was adopted on 11 April 2019. Under this law, cryptoasset service providers established in France will have the possibility to opt into an “optional regime”. If they opt-in, several requirements become mandatory and are locked into the regulatory framework. If instead they decide not to opt-in, cryptoasset service providers established in France will be able to run their activities without being suspected of unlawful conduct in France, but without the badge of regulatory approval. This regime is expected to improve cryptoasset firm access to traditional financial services, while bringing transparency and competitiveness to the market.

- Germany. The Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) issued a set of guidelines in January 2020 covering prospectus and authorisation requirements for cryptoassets. They extensively deal with the nature of cryptoassets, officially classifying them as a security under the Prospectus Regulation. Additionally, all cryptoasset issuers working in the German market, irrespective of their location, are required to be licensed by BaFin. Previously, the regulator had published a guidance document on asset tokenisation that clarified what may qualify as a capital investment according to the Securities Law, explaining how tokens may be treated under the applicable German laws.

- Malta passed a bill in 2018 that introduced a comprehensive regulatory framework for cryptoassets and blockchain technologies, gaining the moniker of ‘blockchain island’. Its reputation, however, was tainted over time due to money laundering concerns expressed by the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and by the departure of cryptoasset firms from the island on grounds of inefficiency.

- Switzerland. The Swiss Federal Council has adopted the DLT/blockchain dispatch. In November 2019, the Swiss Federal Council published a draft bill aimed to further improve the framework conditions for DLT/blockchain firms and applications. The dispatch proposes specific amendments to nine federal acts, covering civil securities, insolvency and financial market law. It introduces DLT/blockchain uncertificated securities in the Swiss Code of Obligations that serve the same functions as traditional securities or centrally registered book-entry securities, and sets out rules for their establishment, transfer and cancellation. Such assets will then enjoy protection similar to that granted to traditional certificated securities. The dispatch further regulates the segregation of crypto-based assets in the event of bankruptcy in the Federal Law on Debt Collection and Bankruptcy and harmonises the provisions of the law on the insolvency of banks accordingly. The draft bill also introduces DLT/blockchain trading facilities as a new regulatory licence category in the Financial Market Infrastructure Act, defined as a professionally operated venue for the multilateral trading of DLT/blockchain securities – allowing such platforms to trade, store and transfer crypto-based securities to regulated financial market players and private customers. The dispatch has been examined by the Swiss Federal Parliament (both parliamentary chambers) over the course of 2020, and has been endorsed by it. The Act will enter into force in 2021.

- Liechtenstein has taken a different approach towards regulating the token economy. The Blockchain Act provides entrepreneurs and consumers alike with a token-specific regulatory foundation. Having started the working group for the Blockchain Act in 2016, Liechtenstein has created legislation focused on equipping innovators with legal certainty and providing a basis for allowing the general public to trust these new technologies. The Blockchain Act tackles the digitalisation of finance and integrates efficiently with the legal framework of both Liechtenstein and the European Union. This proactive approach recognizes that the object of DLT decentralized systems is to omit unneeded intermediaries, but at the same time, recognizes that certain intermediaries are necessary to ease the transition from traditionally centralized and regulated intermediaries, to a peer-to-peer technological world.

Also a number of emerging markets are embracing the new technologies and gearing up their legislations:

- Russia. In July 2020, the Russian President signed a new law on digital financial assets, digital currency and a number of amendments to extant Russian legislation.4 The Digital Financial Assets Bill includes restrictions on the use of cryptoassets and mandates the Central Bank of Russia and the Government to determine ways in which cryptoassets can be used. The law provides conditions relating to token offering and issuance, while maintaining ICOs outside the scope of securities law. To launch an ICO an initiative has a number of obligations, including the release of two documents: an investment memorandum and a public offer. The Digital Economy programme also provides for a number of amendments to the Russian Civil Code that incorporates “digital rights” and “digital money” into the extant regulations.

- Mexico. The Fintech Law gives the Mexican Central Bank the power to determine and authorise the specific type of crypto assets that Fintech Institutions use. In doing so, the Central Bank has to consider a number of general criteria set forth by the Law, including the use to the general public and the regulatory approach in other jurisdictions. Furthermore, the Comisión Nacional para la Protección y Defensa de los Usuarios de Servicios Financieros (CONDUSEF) has statutory powers to issue additional regulations to monitor such entities and ensure equal and fair relationships with their users. The Fintech Law imposed AML/CFT reporting and Know-Your-Client obligations on Fintech institutions and mandated the Secretariat of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP) to publish implementing measures. Fintech institutions, including individuals, are bound by the Federal Law to Identify, Prevent and Eliminate Money Laundering (AML Law) to provide the means to store, protect or transfer virtual assets.

- Nigeria. In September 2020, the Nigeria Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced that the commission is aiming to regulating the crypto industry, to promote market efficiency and transparency and support the crypto market.5 In September 2019, the SEC had set up a committee to propose guidelines on inclusion of cryptocurrency and blockchain technology in the country’s capital market. The Nigerian watchdog viewed cryptoassets as securities, unless the issuers can prove the contrary.

Regulatory sandboxes

Regulatory sandboxes have gained quickly global traction in the Fintech sector. Sandboxes are formal programs that allow for live experiments to test financial services and business models with actual customers, subject to certain safeguards and the regulator's oversight. The report “Early Lessons on Regulatory Innovation to Enable Inclusive FinTech” found that regulatory sandboxes are now either live or planned in over 50 jurisdictions. Ultimately, the sandboxes can provide policymakers with concrete experience and empirical evidence to shape the regulatory framework.

- The UK has been a frontrunner with a strong institutional commitment to Fintech. Early in the market development, at the end of 2015, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) – the British market regulator – published a report that explained why a regulatory sandbox was needed. Since the UK FCA’s regulatory sandbox first started accepting applications, it has seen over 30% of companies accepted into the different cohorts use DLT or provide cryptoasset related services.

- Abu Dhabi Global Market provides another leading example, working with cryptoasset firms in their sandbox. The goal is to test the Spot Cryptoasset Framework and consolidate the legal understanding of cryptoasset products.

- Bank of Lithuania’s LBChain has allowed the central bank to form expertise on the DLT technology, while sharing information and insights with the firms accepted in the sandbox.

Self-regulation

A potentially important area of regulatory development is represented by self-regulatory initiatives, promoted by the crypto industry. In these initiatives, there may be tension between the potentially better insight and expertise owned by the players on the one hand, and the possibly distorted incentive in designing rules that protect the industry-insider interest rather than consumers on the other hand. Generally, the industry seems to be keen to have better regulation in place that would allow for consumer and investor trust, and rapid growth of the crypto market. From this point of view, “enforced self-regulation” represents an interesting solution to the dilemma, in which self-regulation occurs under the aegis of an official mandate delivered by regulators that can also provide additional enforcement.

The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance has identified only two self-regulatory initiatives:

- The Japan Virtual Currency Exchange Association (JVCEA) is a self-regulatory body that was approved by the Japanese financial regulator as a self-regulatory body with oversight on cryptoasset activities in October 2018. It has several responsibilities that include setting industry standards, conducting on-site inspections, and collecting data from its members.

- The Investment Industry Regulatory Organisation of Canada (IIROC), the Canadian self-regulatory organisation, has listed the preparation of regulation for blockchain applications and digital assets among its priorities.

Also, industry groups that have not been directly involved in regulation and monitoring can help to shape the new framework. For example, the Virtual Commodities Association Working Group in the US has been actively contributing to the developing industry standards and best practices in collaboration with regulators.

Conclusions

Regulators in both developed and developing economies are putting in place new regulatory frameworks to build trust and provide investors and consumers with legal protection. With very few exceptions, regulators are not trying to stifle innovation, but are instead motivated by the idea that cryptoassets have the potential to provide value to consumers and investors. Such an effort is in the interest of the consumers and ultimately of industry. Indeed, a robust regulatory framework allowing for trust in these new electronic assets can expand the market and thus increase their value.

Bibliography

Houben, R., Snyers, A., Crypto-assets (2020) – Key developments, regulatory concerns and responses, Study for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament, Luxembourg.

Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance - Apolline Blandin, Ann Sofie Cloots, Hatim Hussain, Michel Rauchs, Rasheed Saleuddin, Jason Grant Allen, Katherine Cloud, and Bryan Zhang - (2019), “Global Cryptoasset Regulatory Landscape Study”, Cambridge Judge Business School

The Law Library of Congress (2018) Regulation of Cryptocurrency Around the World. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/cryptocurrency/cryptocurrency-world-survey.pdf

The Law Library of Congress (2014) Regulation of Bitcoin in Selected Jurisdictions. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/bitcoin-survey/regulation-of-bitcoin.pdf

G7 Working Group on Stablecoins (2019), “Investigating the impact of global stablecoins”, October.

BIS, (2019) Investigating the impact of global stablecoins, A report by the G7 Working Group on Stablecoins, www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d187.pdf

FSB, Addressing the regulatory, supervisory and oversight challenges raised by “global stablecoin” arrangements: Consultative document, April 2020, www.fsb.org/2020/04/addressing-the-regulatory-supervisory-and-oversight-challenges-raised-by-global-stablecoin-arrangements-consultative-document/

European Central Bank (ECB), (2020), A regulatory and financial stability perspective on global stablecoins, Macroprudential Bulletin https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/financial-stability/macroprudential-bulletin/html/ecb.mpbu202005_1~3e9ac10eb1.en.html#toc8

UNSGSA FinTech Working Group and CCAF. (2019). Early Lessons on Regulatory Innovations to Enable Inclusive

FinTech: Innovation Offices, Regulatory Sandboxes, and RegTech. Office of the UNSGSA and CCAF: New York, NY and Cambridge, UK. https://www.unsgsa.org/files/2915/5016/4448/Early_Lessons_on_Regulatory_Innovations_to_Enable_Inclusive_FinTech.pdf

Footnotes

1 The Reserve Bank of India, had banned crypto transactions in 2018 after a string of frauds in the months that followed Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to ban 80% of the country’s currency. Cryptocurrency exchanges in the country responded with a lawsuit in the Supreme Court in September of that year, and earlier this year saw the institution side with them and overturn the move. https://www.cryptoglobe.com/latest/2020/09/india-is-reportedly-planning-to-ban-cryptocurrency-trading/

2 The EU Digital Finance Package can be found at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_1684?mc_cid=93fb2a931d&mc_eid=2fdc615c5d

3 The 5th EU Anti-money Laundering Directive (5AMLD) of the European Parliament and of the Council on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018L0843

4 See, for example, https://www.debevoise.com/insights/publications/2020/08/russia-adopts-law-on-digital-financial-assets

5 The SEC announcement https://sec.gov.ng/statement-on-digital-assets-and-their-classification-and-treatment/