Stablecoins are cryptocurrencies that are designed to reduce price volatility. Their design is motivated by the fact that price stability is a necessary condition for a cryptocurrency to act as a unit of account and store of value, two of the fundamental properties of money. They can therefore encourage participation in cryptoassets from a wider set of investors.

With this in mind, stablecoins are useful for traders who want to hedge against the price volatility of more well-known cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, without resorting to fiat currencies. On the other hand, stablecoins pose a challenge for central banks around the world. If they achieve mass adoption and people prefer to hold them instead of fiat currencies, the effectiveness of monetary policy by central banks would be greatly diminished, together with their ability to receive seignorage revenue. It is therefore no surprise that many institutions are starting to take notice. The G7, for example, recently published a report on stablecoins1.

The price target of a stablecoin is usually measured with respect to a fiat currency, such as the US Dollar, or even a basket of currencies, as it is the plan for Libra2. There are over 50 stablecoins3. In this note, we concentrate on three classes of stablecoins, which differ in terms of their mechanisms for providing price stability.

Custodial Stablecoins

Custodial, or collateralised off-chain, stablecoins are explicitly backed by a fiat currency. However, they rely on a trusted intermediary, or issuer, that safeguards the reserves of the currency. This adds an element of centralisation in the network, which may be undesirable. The mechanism works as follows. An investor deposits $1 to the issuer, in exchange for one unit of the stablecoin. The issuer holds the US Dollars in a vault or bank account, releasing them only when an investor sells a unit of the stablecoin back to them. The main problem with this approach, however, is that investors need to trust the issuer of the stablecoin, and the incentives of the two parties do not always coincide.

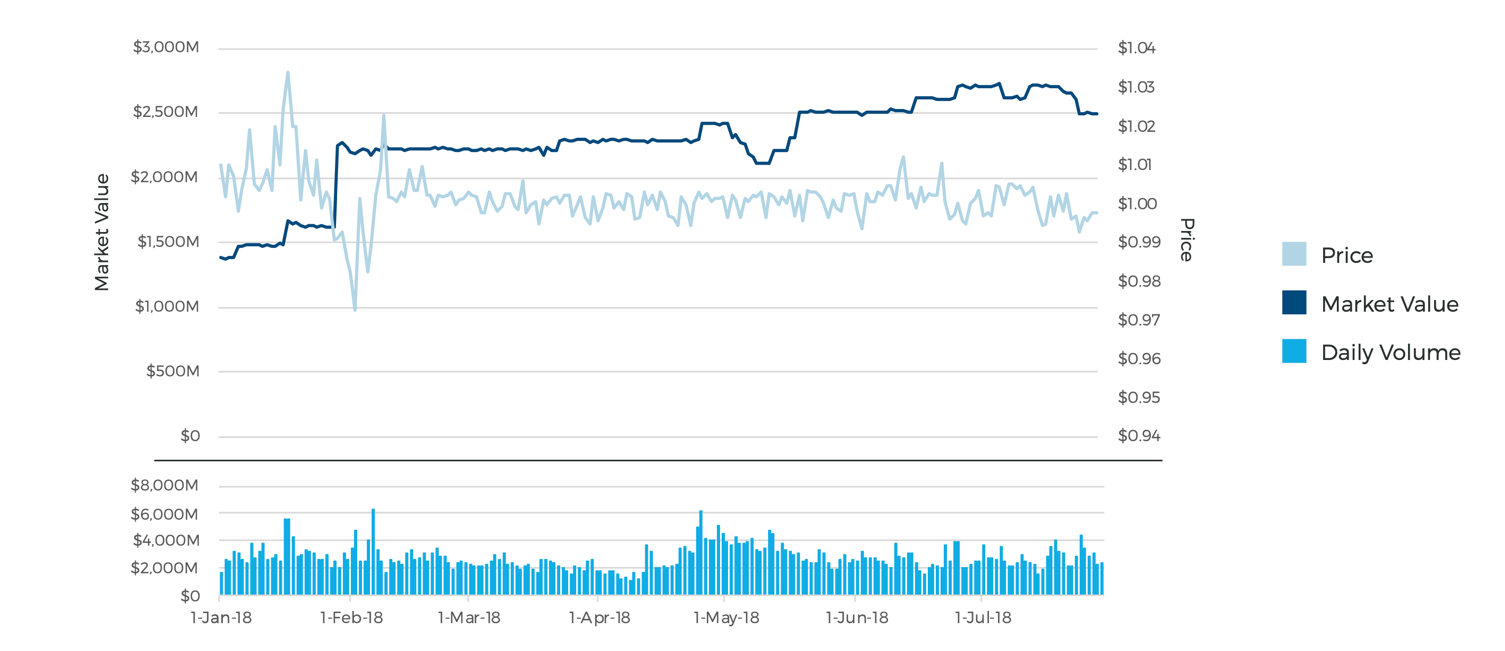

For example, the issuer has an incentive to loan the US Dollars, instead of keeping them in a vault or a bank account, in order to earn a higher interest. If the loans are not repaid due to defaults, or there is a sudden demand for redeeming the US Dollars by investors before the loans are due, investors may find difficult to exchange their stablecoins. This would lead to a drop in their price. Alternatively, the issuer could issue more stablecoins than the US Dollars that they have, which could also lead to a decrease in price if it becomes common knowledge. For example, Tether4, which is the largest (by market cap) custodial stablecoin and the second most traded, after Bitcoin, has often been accused of not being transparent about its auditing process. This has prompted speculations that the amount of Tether may not backed by enough US Dollars. The graph below shows how the price of Tether has fluctuated over the last few years. The price of Tether can also rise above $1 if, for example, there is a sudden increase in its demand that cannot be met given the current liquidity in the market. However, note that in general the price of Tether has remained very close to its target price.

Figure 1: Tether

Noncustodial Stablecoins

Noncustodial, or collateralised on-chain, stablecoins comprise another interesting class. Their main advantage is that they do not rely on a trusted intermediary that holds a fiat currency as collateral, off-chain. Both the execution and collateral (in the form of another cryptocurrency) are on-chain, thus minimising the counterparty risk. However, they are more vulnerable to attacks, which could lead to a price that is very different from the target, rendering it useless. The most well-known example of this class is Maker Dao5.

To explain the mechanism, consider a stablecoin whose aim is to retain its price as close as possible to $1. There is also another cryptocurrency, for example Ether, that acts as a collateral. The price of Ether is exogenous and can depend on many factors, whereas the price of the stablecoin is endogenous and targeted towards $1. The price of Ether is recorded by an oracle on the chain. However, this element reduces the decentralisation and trustlessness of the environment.

There are two types of traders. Holders prefer to hold the stablecoin and achieve price stability. Speculators aim to maximise their profits by insuring the holders. The speculators deposit Ether as collateral, in order to borrow newly created stablecoins that they can then sell to holders. The collateral is locked in a smart contract, and is released when the stablecoins are returned and destroyed. If the price of Ether does not fluctuate very much, the collateral is enough to cover the loan in case it is not paid back. Moreover, if the price of Ether starts dropping, the smart contract demands more collateral, otherwise it liquidates Ether, before its price drops below the value of the loan.

Under mild price movements for Ether, this mechanism works well. If the price of the stablecoin drops below $1, there is an incentive from the speculators to buy stablecoins in the open market in order to repay their loan. The repaid stablecoins are destroyed, and the speculators receive the collateral. As a result, the supply of stablecoins is reduced and their price increases. If the price of the stablecoin rises above $1, then the speculators have the incentive to borrow more stablecoins and sell them in the open market, thus increasing their supply and reducing their price.

The price stability mechanism can increase or decrease the interest rate for the loans, in order to incentivise the speculators to buy or sell stablecoins. For example, if the price starts dropping fast, an increase in the interest rate, or stability fee, will incentivise the speculators to repay their loans. However, if their expectations are that the price will decrease even further, for example because of a speculative attack, they may start selling their stablecoins, precipitating a further drop in price. The danger then is that expectations become self-fulfilling, leading to a collapse of the price and of the usefulness of the stable coin. This risk of collapse can also materialise if the price of Ether drops too fast. The smart contract will demand an increase in collateral, or settlement of the loan. If speculators do not respond fast enough, the collateral could become less valuable than the loan, to the point where they have no incentive to repay the loan. If all speculators try to settle their loans simultaneously, then they will increase their demand for stablecoins, thus increasing its price. This will dry the liquidity, leading to further increases in price. At the same time, as the price of Ether decreases, there will be a “flight to safety”, as holders will dump Ether in order to buy more stablecoins.

In order to avoid these wild swings of the price of the stablecoin, the network prescribes the process of a global settlement, where all stablecoins are destroyed and collaterals are returned. This is triggered by a vote from the stakeholders of the network. However, this creates a further element of centralisation of the network, which is also undesirable.

Seigniorage Shares

The last class of stablecoins is called “seigniorage shares” and tries to implement the following simple idea. If the price of the stablecoin increases above $1, then more stablecoins are created, such that the increased supply decreases the price. If the stablecoin’s price decreases below $1, some stablecoins are “destroyed”, such that the reduced supply increases its price. In other words, a change of X% in the price of the stablecoin is met with a change of X% in its quantity and in the same direction.

Although this is a simple idea that avoids the need for a collateral, either on or off-chain, its implementation has two problems. First, how can we ensure that the price of the stablecoin is reported accurately and truthfully in the blockchain? We need an oracle which, as with previous classes of stablecoins, introduces an element of centralisation that is undesirable.

Second, when the supply of stablecoins increases, who receives the extra stablecoins? Similarly, when the supply decreases, whose stablecoins are destroyed? One simple answer is to distribute the gains or losses pro-rata. For example, suppose that there is increased demand and the price of the stablecoin goes to $2. Then, the supply is doubled and an individual with 10 stablecoins now has 20. The problem with this approach is that, although the price of the stablecoin remains stable, the individual’s wallet has now doubled in value, from $10 to $20. Similarly, if the price was $0.5, the supply would be halved and the individual would end up with 5 stablecoins, worth $5. Because the value of the individual’s wallet is not stable, such a stablecoin cannot act as a store of value, violating one of the basic properties of money.

One solution to this problem is provided by the stablecoin Basis6, which implements a three-token system, consisting of Basis, shares and bond tokens. If the price of Basis drops below $1, their supply needs to be reduced. This is done by issuing new bonds, which are offered at a discounted price of Basis, to be determined at an open auction. Each bond promises to pay 1 Basis in the future, when the supply of Basis expands again. Speculators buy these bonds by exchanging them with Basis, which are then destroyed. When the price of Basis increases above $1, the supply of Basis increases and the new Basis are first distributed to all bond holders. When all bonds are redeemed, the additional Basis are distributed to the holders of shares. These shares are tokens that are created at the genesis of the blockchain and are not pegged to some other currency.

Although this project was promising and it raised a significant amount of money ($133M), it was eventually shut down when it became apparent that the bonds and shares tokens would inevitably be classified as securities in the US. Such a classification would introduce many regulatory hurdles, making the network more centralised and the project more difficult to implement.

Concluding Remarks

In summary, these three classes of stablecoins have interesting design characteristics and can achieve price stability, at the expense of introducing some elements of centralisation. However, there are important risks that investors need to be aware of, such as the possibility of a market collapse due to poor auditing practices, significant volatility in the price of the collateral, or regulation.

Bibliography

1 https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d187.pdf

2 https://libra.org/en-US/

3 https://www.blockchain.com/ru/static/pdf/StablecoinsReportFinal.pdf

4 https://arxiv.org/pdf/1906.02152.pdf

5 https://makerdao.com/en/

6 https://www.basis.io/